The Nibi Library: The Mexican Feminine

At Nibi, we believe fashion and literature are both intimate languages: they touch our body, our mind, our imagination.

This new series begins from that premise. Here, reading is not an academic exercise, nor a list of recommendations, it is a form of connection. A way of listening to voices that have shaped cultural sensibility, often from the margins, often at great personal cost.

Introducing the Voice of ourLibrary

Our Literary Curator, Daniela de la Garza Cantú, inaugurates The Nibi Library with “Las siete cabritas” by Elena Poniatowska, which portrays seven of the most influential women artists in Mexican cultural history. It is of great importance to me that the first book we share honors our beginnings. Nibi was founded in Mexico in 2008 by my mother, the first artist I ever admired. She created her own world through her creative intuition, resilience through hardships and powerful softness.

I know this book profiles seven incredible women, but in my book, there are eight. The first is my mother.

Written by Daniela de la Garza Cantú, The Nibi Library, January, 2026:

I found this little, slightly beat-up gem a couple years back in a streetside book market in San Cristobal de las Casas, Chiapas. Although this book was not my formal introduction to most of the women in its pages, it acted as a guiding star to my earliest explorations of art and literature by Mexican women.

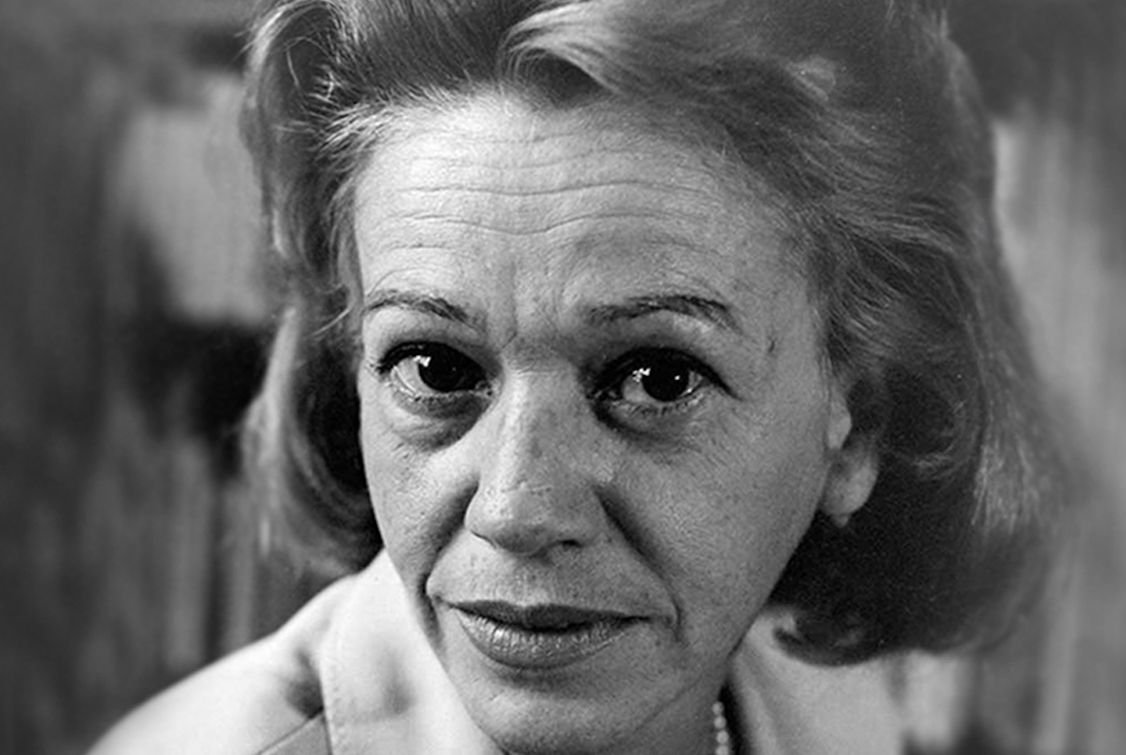

First published in 2000, Las siete cabritas is a brief but incisive essay collection by Elena Poniatowska, one of Mexico’s most important contemporary writers and chroniclers of its social, political, and cultural life. Known for her work at the intersection of journalism, literature, and testimonial writing, Poniatowska brings together seven portraits of women who shaped – and unsettled –Mexico’s modern cultural imagination. The book was later translated into English by Elizabeth Coonrod Martínez under the (somewhat flattening) title The Women of Mexico's Cultural Renaissance.

The Cardinal Points

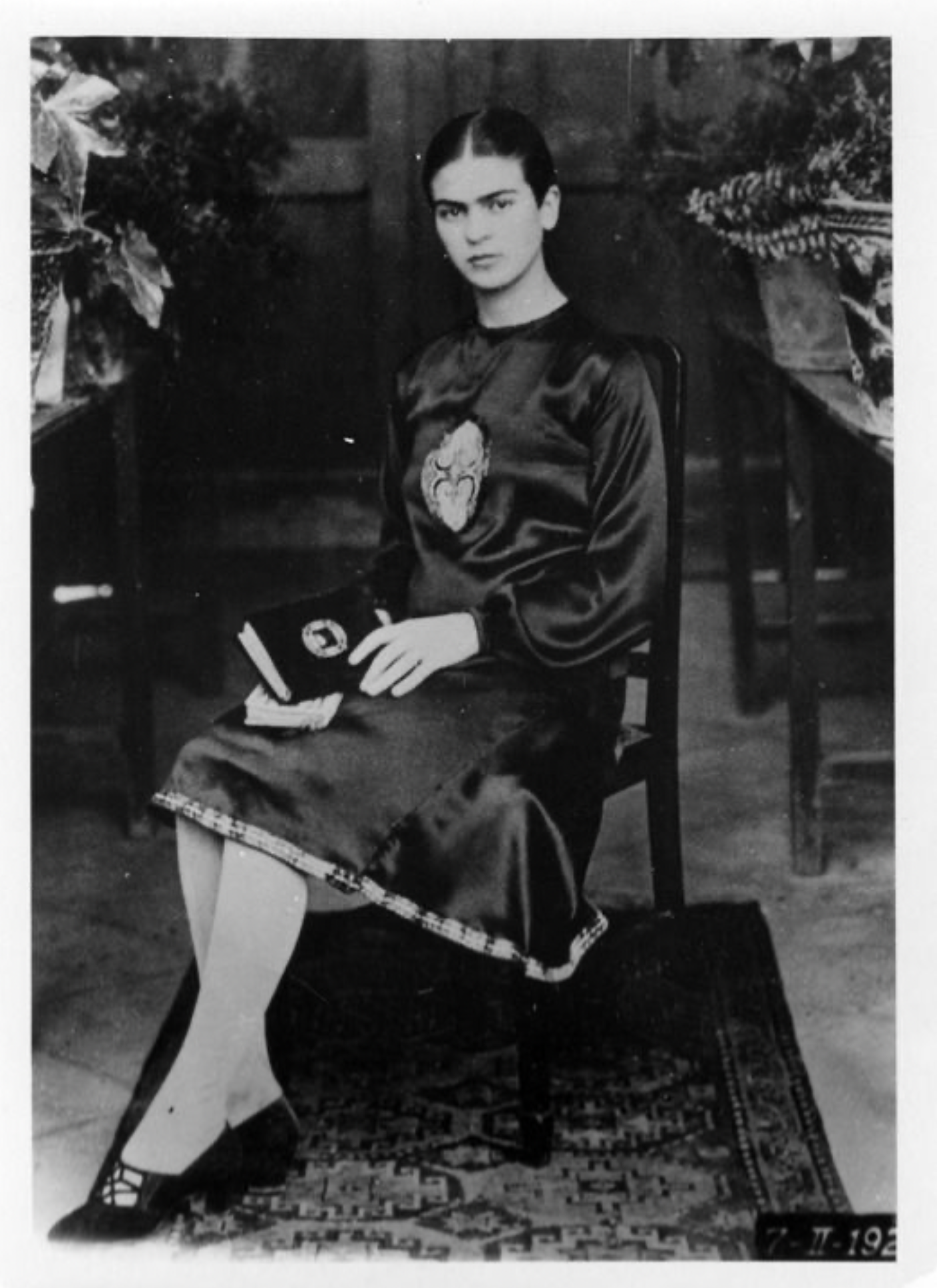

On its first pages, we are invited as voyeurs into a love letter imagined having been penned by Frida Kahlo – painter of wounded, poignant surrealist self-portraits who, surely, needs no introduction. For about a dozen pages, we are privy to her memories of pain – the near-fatal accident, metal piercing through organs; the crooked spine, the barren womb – as well as to her descriptions of love – for Diego Rivera, her frog-prince, but also her family, her friends, the country she helped shape with her palette. There are also her displays of passion – Frida painting in bed, in her wheelchair, Frida painting her flowering injuries, yes, but also Frida at seventeen years old, crossdressing in her backyard, posing tall and imposing in her three-piece suit and unibrow for her family photos; Frida traveling around the world, Frida the lustful, the rebel, the socialist; Frida anxious for life. Finally, there is her tenderness, seeping through everything – Frida and her little monkey, Frida and her baby doe, Frida in her blue house, Frida painting her corsets. It is this quartet – pain, love, passion, and tenderness – that the author calls the cardinal points of Frida’s life.

A fragile butterfly

We then encounter proud, beautiful Guadalupe Amor – Pita – who described herself in her sonnets as “vain, despotic, blasphemous, perverse” – both “a fragile butterfly” and a “hysteric”, rose-skinned, hell-bound, an anathema. Hers is a story of pride, beauty and delirium. The author, Amor’s niece, affectionately anoints her aunt the “Eleventh Muse”, and allows the artist to describe herself: "a bewildered and bewildering being”, “full of vanity, self-love, and sterile and naive ambitions”. We are, however, entitled to doubt the supposed sterility of her ambitions; her legacy, both as the subject and the agent of her own creative force, leaves little room for such claims.

Perpetual Movement

We are then introduced to Carmen Mondragón, early 20th century painter, poet and muse who later adopted the Nahuatl name Nahui Olin, meaning “perpetual movement” or “fifth sun”. Hers is a life oscillating from shroudedness to nakedness, as well as one marked contradictions: first a young, precocious writer denouncing marriage and tradition from within a conservative family, writing from behind a convent school desk; later an energetic, enigmatic woman known more for her transgressive provocations – her nude photographs, her erotic poetry, her many lovers – than for her political ones – her participation in artists’ unions and early feminist organizations. Her drive towards self-exploration, her island-like temperament, her loves and losses, and even her quiet, tragic end, unfold as a tale of both beauty and sorrow.

The Only One

María Izquierdo follows – “the vanguard” –, an artist whose childhood and adolescence was marked by the violence of the Mexican Revolution and an early and cruel marriage, and who then wrote the only chronicle of the war published by a woman and became famous for painting the “essentialist” Mexican – red tablecloths, farm girls, red snappers. She mourned and honored, pre-Columbian art. Diego Rivera famously called her work “the only one”, and, although her legacy was obscured by the “fridomanía” of the late 20th century, her place in Mexican art history endures.

A Contradiction

The author is less generous toward Elena Garro, for understandable reasons. A talented writer long overshadowed by her unhappy marriage to Octavio Paz – who married her before she could finish university and burned her writing – Garro later found herself accused of conspiring with the Mexican government during the 1968 student revolt, betraying many of her left-wing peers in the process. Elena is, no doubt, a contradictory, problematic, emblematic character: vibrant, furious, violently talented. She embodies both victim and perpetrator; the effigy and the stake. Her writing is a blinding, contracting star; if she is to die, she will burn everything in her stead.

Not of her word, but of many words

Rosario Castellano appears in stark contrast to many of these women – an often-unassuming character, acutely opposed to grandiose statements, embarrassed by poetry, but with a quick-witted, alert, beautiful mind. She is my personal favorite: a woman “not of her word, but of many words”; a woman of two worlds, as well, nourished by the cold, cerebral anger of mid-century European feminist theory and the violent, crude realities of a Southern Mexican campo reeling from centuries indigenous exploitation, her childhood home. Deeply sensitive, acutely critical, Rosario Castellano is both a lover and a statuette of solitude, and first and foremost, a tragicomedian. There has been, to my eye, no Mexican writer of the likes of her.

Revolution

This little book finally sets upon Nellie Campobello. Her life was shrouded in an air of mystique and mystery: rumored to have been the daughter of a revolutionary hero, she traveled the country with her sister collecting traditional pre-Hispanic dances as an entomologist would butterflies. Her love for dance and theater then grew her into a playwright, then poet, then chronicler and novelist. Hers is what would seem like a beautiful contradiction – both ballerina and chronicler of violence – but this is, precisely, the heart of her mexicanidad. Our government still fondly recalls one of her most famous works as a choreographer, in which children danced representing the Mexican people, and she, the Revolution.

Conclusion: On Inheritance and Making

The thread that unites these women, far from their place in the field of art, or their nationality, is the sense of them being at once violently ahead of their time – proudly, fascinatingly and often painfully sticking out of the jigsaw puzzle that was 20th century Mexico – while also firmly lodged in it, with a foundational presence in the country’s modern cultural identity, without which we Mexicans would be no better than orphans, unmoored.

At Nibi, we are interested in this same tension: between inheritance and rupture, tradition and refusal. Just as these women stitched new imaginaries into a resistant cultural fabric, we think of making—whether garments, spaces, or ideas—as an ethical act of continuity and transformation.

To read Las siete cabritas is to be reminded that femininity is not singular, polite, or resolved. It is excessive, contradictory, wounded, ecstatic, and unfinished. It moves—like cloth on a body, like language in time.

And perhaps this is what reading, like dressing, can offer us: not answers, but a way of standing more fully inside ourselves.